Peugeot 106 electric. Part 1: disassembly

This is a story about my Peugeot 106 electric, bought 2026-01-12.

The Peugeot 106 electric is one of the first electric cars, produced between 1995 and 2003. It is a remarkably simple car, containing just the bare necessities.

Some interesting facts:

- In the Netherlands, there exists only one 106 electric that is legal to drive. Hopefully I will have number two!

- It has an 11kW electric motor, which can bring the car from 0 to 80km/h in a slow and steady 25 seconds.

- It has a fully galavanized frame

- The fuel gauge has been replaced by a power meter (“econometer”)

- The tachometer has been replaced by a battery charge meter

- It has no gear lever, not even PRND like cars with an automatic transmission. It only has a button to toggle the “Reverse” mode. Since the motor has no permanent magnets, you can turn the wheels by hand when powered off. Effectively, this is “neutral”.

- It still has a small fuel tank, for the interior heater.

Buying my 106 electric

I bought a 106 electric for €1900. It is a white 5-door version. It is not in a driveable state, but it is physically in good condition. This particular car was imported to the Netherlands in 2016 with 31954 km. In 2020, it was sold with 69022km and it has not driven since.

The person we bought the car from was seemingly unable to tell the truth. He insisted on his ficticious numbers even where easily verifiable otherwise. Like the odometer (“only 7000km”, actually 69000), the maximum speed (“easily 140km/h”, actually 90km/h), the power (“80pk but it’s electric so even more”, actually 27pk). He claimed everything about the car was original and that it had not been “messed with”. We quickly spotted a 3D-printed housing with a touch screen, stuck to the dashboard with double sided tape. When confronted with this he again insisted this was a completely original part. This was a strange experience. It felt like being scammed. Still, I wanted the car and I think I paid a fair price for it, ignoring any false promises by the previous owner. I fully expected needing to do major repairs, like replacing the batteries with LiFePO4. It was only important that the mechanical parts and interior were in good condition, which was the case.

Disassembling the batteries

On the dashboard we noticed a 3D-printed housing with a touch screen. Someone has probably already replaced the batteries.

It turns out this is part of the EVMS2 (Electric Vehicle Management System), a product by Zero Emission Vehicles Australia, a business that has unfortunately closed down. They made, among other things, different versions of these EV magement systems for the purpose of converting cars with a combustion engine to electric. The monitor connects to the EVMS2 Core, which connects to BMS12 modules for monitoring cells. We went looking for these modules.

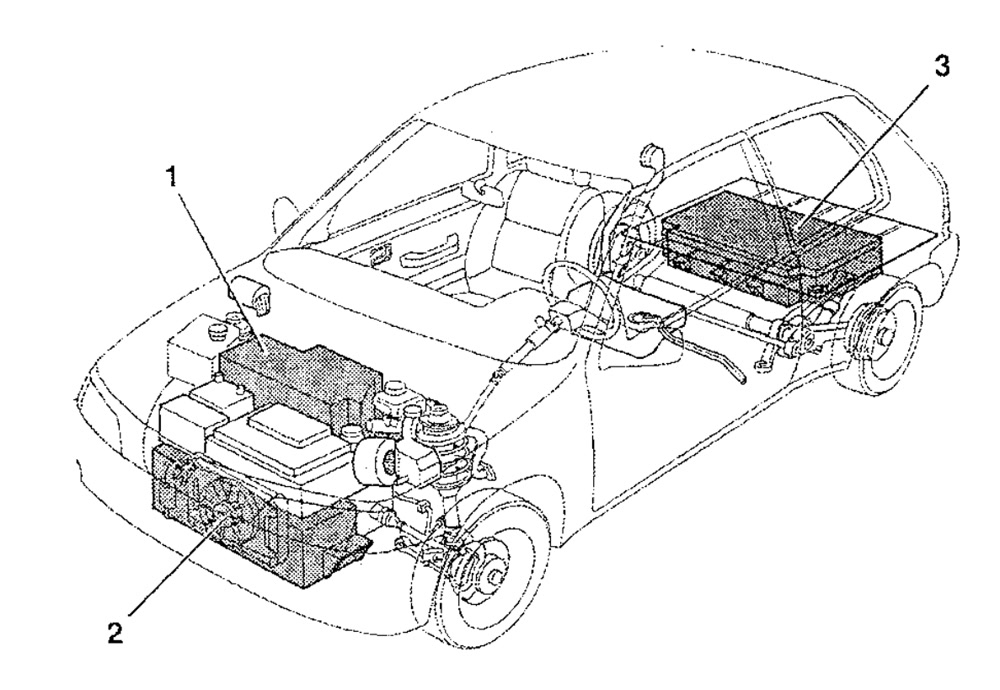

The car has 3 battery compartments.

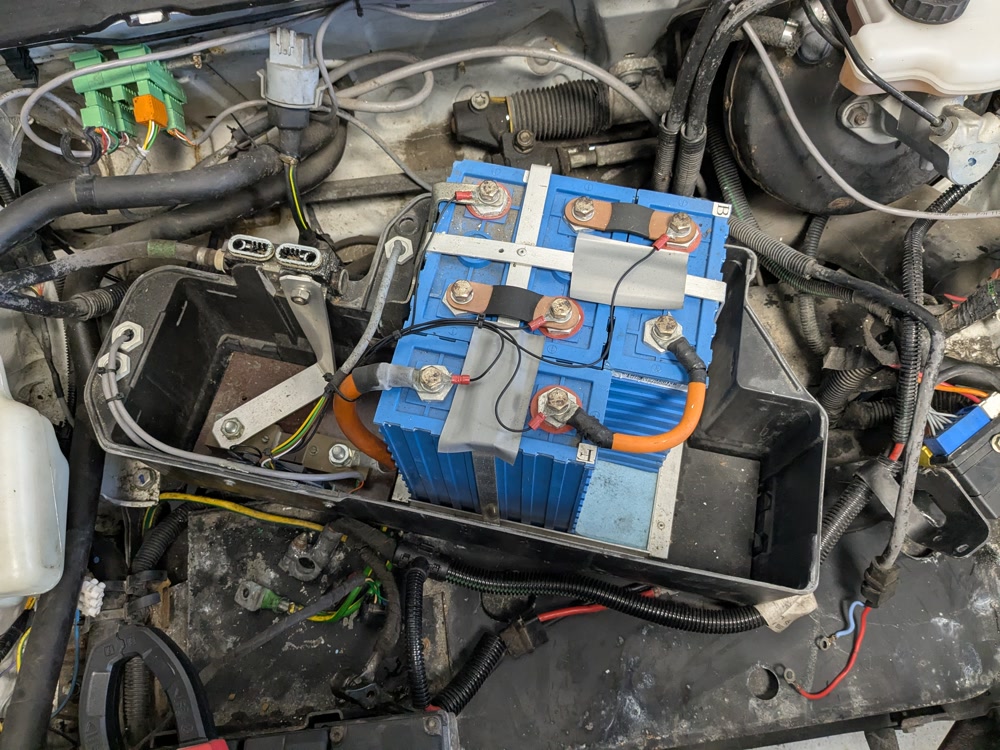

Our suspicions were confirmed when we opened up the first battery casing. We saw 4 CALB LiFePO4 modules. For some reason there was also an unused current measuring shunt. The cells are at 0.0V, so they are completely unusable. We can hopefully reuse the BMS12 modules. The EVMS seems to be a perfect fit, it would be great if we don’t need to spend money on a new BMS.

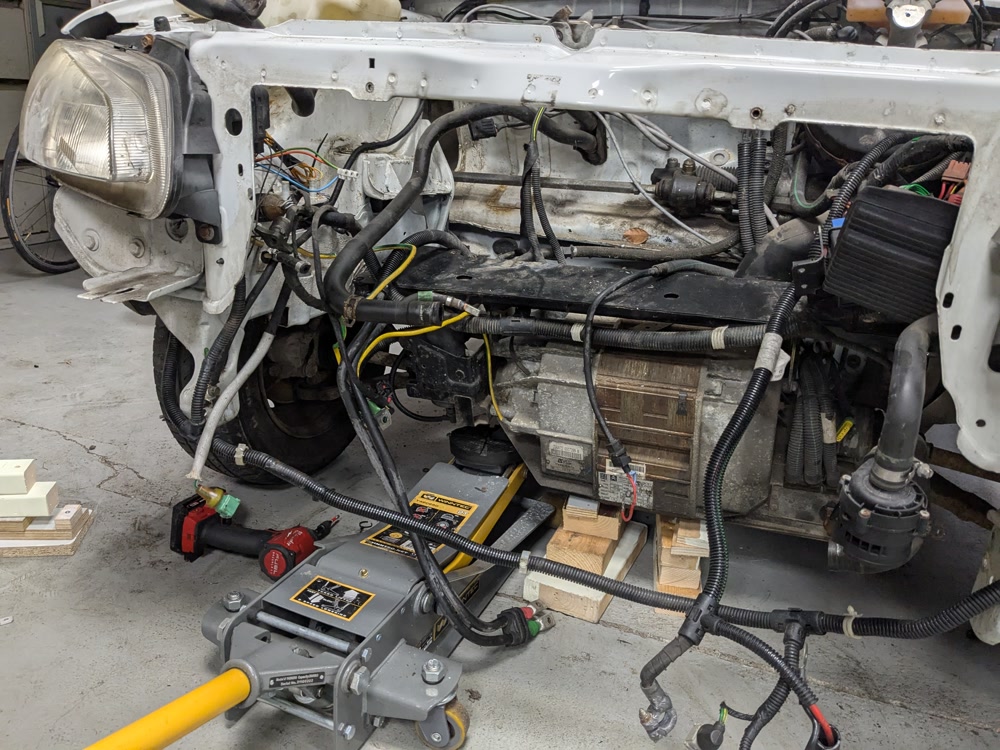

Enthousiastically I unscrewed more bolts, only to find out that I accidentally unfastened a beam to which one of the two motor mounts was attached. The motor was now partially resting on some cables and the lower battery… After removing the lower battery we could attach the motor properly again. Fortunately, I did not cause any damage.

Finally, it was time to remove the rear battery.

This battery was assembled most “professionally”. It had nice plastic separators and the batteries were tightly held in place using foam. There was even an attempt at compressing the batteries, using threaded rod and aluminium parts. The aliminium parts are not strong enough to excert much force on the batteries, but still I appreciate an attempt was made.

Someone really put a lot of work in building these batteries. It is unfortunate that they are now at 0V and have to be thrown away. The previous owner (not the person who built these batteries) did not drive it at all for 6 years, so it is likely that the batteries just slowly drained flat.

The original batteries were 20 x 100Ah 6V nominal (12kWh). There are no markings on the new batteries, but I guess they are 200Ah LiFePO4. That gives 44 x 200Ah 3.2V (28kWh). The new batteries at 140V nominal had a higher voltage than the original batteries, with 120V nominal. Hopefully they didn’t overload the motor and cause damage.

Disposing of the original batteries

I am left with a pile of chemical waste that no one wants:

I tried bringing it to the local municipality waste disposal. They did not enjoy my pile of batteries. Apparently it’s was the first time an individual has replaced the batteries in their electric car and tried to dispose of them there. Who would have guessed? They referred me to a business which I would have to pay to come pick up my batteries. Obviously, this is something I would rather avoid.

Fortunately, I found out about a law here in the Netherlands regarding electronic equipment, dictating that any business who sells electronic equipment should also take back old equipment at no charge. I wasn’t sure whether batteries qualified as electronic equiment under this legislation so I sent an e-mail to the battery supplier (NKON). They confirmed they are indeed required by law to accept my batteries. When I pick up the new batteries I can just make my old batteries their problem. Problem solved.

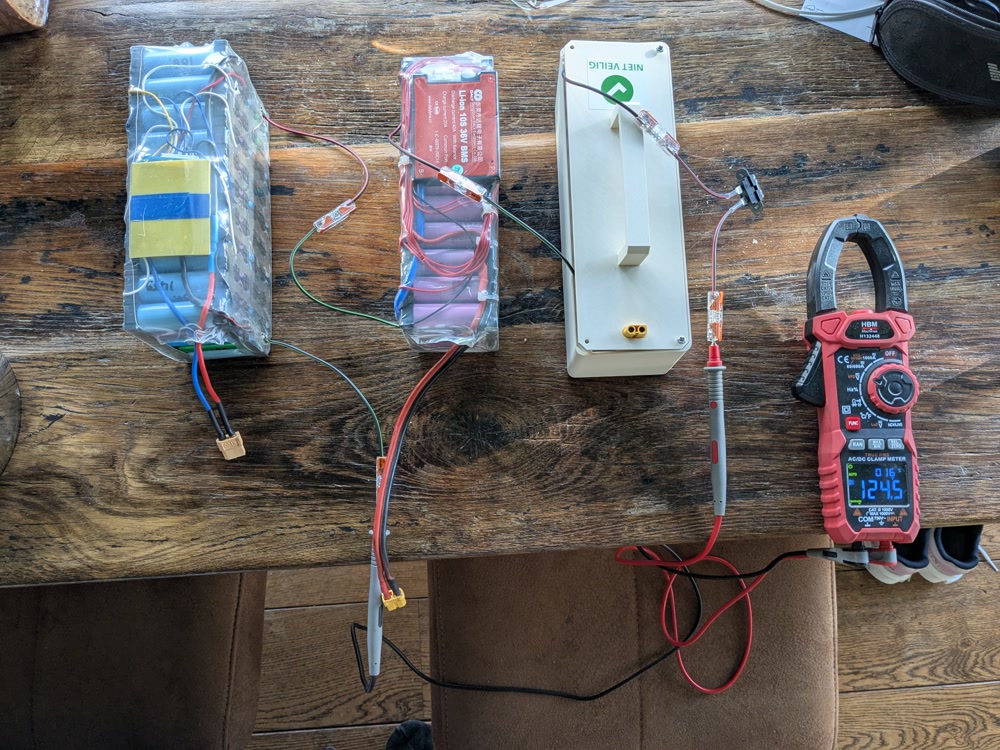

Testing the electronics

Before investing in to new batteries, we want to see if the motor and electronics still work by hooking up 3 10S Li-ion e-bike batteries in series. Fully charged that gives a little over 120V which should work. These ebike batteries can easily provide 30A which should be enough for a brief test. It is not possible to hook up batteries with a BMS in series. If the mosfets in one BMS switch off, the mosfets in the other BMS modules get a high voltage across them and may blow up (I speak from experience!). Therefore, we will bypass the BMS for this test.

It works!! This is a huge relief. Replacing the electronics would be expensive.

New battery

I ordered 40x Eve MB31 cells for €2798 on 2026-01-23. The delivery estimate is 2026-03-06.

Specifications:

- Voltage: 3.2V (2.5V - 3.65V)

- Capacity: 314Ah 1004.8Wh (total: 40kWh)

- Max continuous charge power: 500W (total: 20kW)

- Max continous discharge power: 500W (total: 20kW)

- Weight: 5.6kg

- Dimensions: H:207.2mm L:173.7mm T:71.7mm

- Storage temperature: -20 - 45C (preferably 0 - 25C)

- Storage state of charge: 15 - 40%

- Charge temperature: 0 - 60C

- Discharge temperature -30 - 60C

- Lifetime: after 8000 cycles at 25C, 70% capacity remaining

With 40kWh this battery pack will be much larger than the original pack, at only 12kWh. Originally, it was claimed to have a 80km range with 12kWh battery: 150Wh/km. At this efficiency, I should be able to achieve a range of 260km using the new battery pack. Maybe I will even get a bit more, due to the lower internal resistance of the new batteries. It is worth noting that the 106 has a fuel-powered heater, so in the winter it does not consume extra electricity for heating. It will still have a slightly reduced range, because the batteries diminish in performance at lower temperature (higher internal resistance).

The cycle life is impressive. Let’s assume a cycle life of 3000 instead of the manufacturer’s promised 8000 due to the lack of temperature control. Using the previously estimated range of 250km, this gives a potential lifetime of 750.000km. It would be the most anyone has driven this car so far.

In the next two months I will perform various small repairs, while waiting impatiently for the new cells to arrive.

Last updated: 2026-01-25